Vicky Kelman

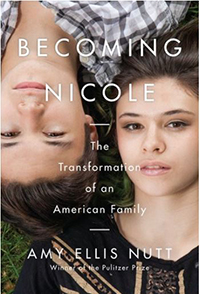

Becoming Nicole: The Transformation of an American Family by Amy Ellis McNutt

“Hanokh l’na’ar al pi darko / gam ki yazkin lo yasur mimena” ( Proverbs 22:6)

This biblical teaching has been ringing in my brain since reading “Becoming Nicole.”

The most usual translation for that proverb is

“Train (educate) a lad (young person) in the way he/ she ought to/ should go; he/ she will not swerve from it even in old age.”

But a more accurate translation of the phrase “al pi darko” (in the first half of the verse) would actually be “according to his ( her) way.” The word darko definitely means “his way.” And there is more than a difference in nuance. The standard translation indicates that there is right way somewhere out there that determines the “should,” the prescribed path to be taken. (Of course, this being the Bible, darko = his way, could also be darko, His way, but I did not run across any commentaries pointing that out.)

The translation I suggest, emphasizes that the way to educate is to discern the child’s way and follow from there.

The book, Becoming Nicole: The Transformation of an American Family, by Amy Ellis Nutt, is a portrait of a family that was able to raise two children in accordance with this teaching, in very unusual and trying circumstances. Wayne and Kelly Maines, unable to conceive after five years of marriage, have the amazing luck to be able to adopt newborn identical twin boys (well, to be exact, they had thought they were adopting one baby—who turned out to be two—and they had another surprise waiting that didn’t begin to manifest itself immediately.) They named their new sons, Jonas and Wyatt.

The book, Becoming Nicole: The Transformation of an American Family, by Amy Ellis Nutt, is a portrait of a family that was able to raise two children in accordance with this teaching, in very unusual and trying circumstances. Wayne and Kelly Maines, unable to conceive after five years of marriage, have the amazing luck to be able to adopt newborn identical twin boys (well, to be exact, they had thought they were adopting one baby—who turned out to be two—and they had another surprise waiting that didn’t begin to manifest itself immediately.) They named their new sons, Jonas and Wyatt.

The family settled in a conservative, family-oriented rural town in upstate New York. The boys’ adoptions became legal at seven months and life unfolded in a fairly predictable fashion, until….

Everyone began to notice that these identical twin boys were not so identical. As they grew into toddlers, differences began to develop in their styles of play. So far, not so different from patterns observed with most twins and siblings. But their styles begin to diverge further and further and with some clearly observable consistency. “Wyatt loved everything Barbie while Jonas loved everything Star Wars. The biggest difference between the boys could be seen in the characters they chose when they acted out stories. Jonas was always the “boy” character and Wyatt the “girl” character. He loved playing Cinderella, Dorothy from the Wizard of Oz, Wendy from Peter Pan and Ariel from the Little Mermaid.” Then, at age 3 in a moment of closeness with Wayne, Wyatt tearfully tells his father that he hates his penis. (chapter 3)

“How do we understand what al pi darko means here? Wayne and Kelly are baffled, especially Wayne who has been thinking along very traditional fatherhood role lines about things such as playing football and hunting with “my boys.”

As she struggles to understand Wyatt, Kelly is more open to finding out what darko/his way,” might mean. Wyatt was just “different” is how she explained his behavior to friends and family, initially. “She knew most others didn’t understand, especially Wayne. She’d seen her husband sitting reading the newspaper while Wyatt skipped around in his tutu, a hand-me-down from his friend Leah. Wayne pretended not to see him. He didn’t look up. He didn’t want to look up.” (chapter 3)

Wayne just wanted a normal family like the one he had grown up in. Kelly wasn’t sure there was such a thing as “a normal” family. The family she grew up in had not been like other families she knew. Unsure there even was a “normal” family, she wasn’t struggling against her expectations, as Wayne was.

Kelly struggles on with how to parent Wyatt and Jonas, how to discern who they each are as individuals—as well as with the “absence” of Wayne from shared parenting duties, especially those involving Wyatt..

Kelly faces the daily clash over clothing with Wyatt. She perceives it to be cruel to dress Wyatt in clothing he hates. At first, as a compromise position she searches for plain, as opposed to frilly, clothing in the bright colors he seems to crave. She makes that first purchases with hesitation, without consulting Wayne who doesn’t approve but doesn’t try to stop her.

“Why do you have to indulge him? Wayne would ask.

He’s trying to tell us something, “Kelly would say. “He’s showing us who he is, and we’ve got to help him figure it out.” (chapter 4)

All children need this kind of close loving attention from an adult who means something to them.

One night, Kelly sits down at her computer, and inputs the phrase “boys who like girls’ toys” and what she discovers there kicks off her own educational journey to discover who Wyatt is.

The rest of this fascinating book tells the story of Wyatt’s emergence as Nicole and follows Nicole and Jonas as far as college, an eventful journey encompassing acceptance and joy, discovery, cruelty, prejudice, transformation and growth, and a history making court case.

McNutt not only tells the family’s story but provides rich information. She devotes a lot of space to biology and definitions so that we come to understand the bigger human picture of which the Maines are an example. Genitals and gender identity develop differently in utero. Gender identity develops in the brain, and usually, but not always, correlates with the genitals. For those in the minority, the struggle to live in a body that feels like the wrong body is intense and painful (chapters 14, 15, 16) “Sexual orientation is who you go to bed with. Gender identity is who you go to bed as.” (chapter 16)l

Becoming Nicole, should be required reading for parents and teachers, not because so many of us will raise transgender children, although we will all encounter them one way or another, but because it models al pi darko, so clearly. Kelly and Wayne, though their pacing and timing are exceedingly different and their evolutions follow very different trajectories, are models of what it means to educate, guide, parent a child Al pi darko.. Kelly moves first, taking a stance of curiosity almost from the start. Wane is slower out of the starting gate and his path is more rocky, but both can be role models for us.

Jonas is the family member who is least revealed. I came away from the book feeling I barely knew him. Jonas says that he knows no other reality than this sibling who was Wyatt and is now Nicole. He had no other expectations. Who Nicole is doesn’t seem to surprise him or challenge any assumptions. She is who she is. His sister. Given that being a twin of a more ordinary sort is complicated enough—I kept wanting to hear more from him.

In his famous Haggadah, the artist David Moss represents the four children (sons) as playing cards, commenting that parents are dealt their children almost by chance, as we would be dealt a hand of cards. We get the children we get. It’s always a surprise—and we a step up to task of playing that hand. Kelly and Wayne model that for us.

We learn from the Maines’s story that a large part of the parenting job here is also advocacy for the child in the world “out there.” The interface with extended family, neighbors, church and school system (and think: youth group, summer camp, sports team). Advocacy is a huge part of the Maines family journey (in ways that echo the experience of all parents of kids who have needs that the system is not ready to deal with) but because it deals with gender, it is more fraught and more fear inducing. For the Maines family, the issue that eventually leads them to court is use of the bathroom in school.

Our Jewish community institutions are just starting to confront the issue of inclusion of transgender members. I did a “quick and dirty” little survey of some synagogues, day schools and summer camps and was pleased to discover that although some are further along in the process than others, all are struggling to figure out how to be inclusive and welcoming of this newly identified ( for them) segment of our population. They are juggling many issues at the crossroads of facilities (physical space), legal questions and Jewish tradition.

If you haven’t already, you will soon notice new labels for restrooms in public places*, new choices on questionnaires in addition to the standard “M” and “F,” and much discussion about preferred pronouns. The pink and blue “binary world” of boy/girl, into which this generation of parents and educators (not to mention grandparents) was born is gone forever and this new set of lenses through which to view gender is a huge jolt. McNutt provides an interesting and comprehensive guide to the unfolding of this new aspect of the miracle that is the human race.

For Jewish resources and support: check Keshet, a national organization working for the full equality and inclusion of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender Jews in Jewish life.

front page of the New York Times Styles section for January 30, 2016