Joel Grishaver

Part One

Part One

Jon Landau, famously wrote, “I saw rock and roll future, and its name is Bruce Springsteen.” I would like to say, “I have read the future of Jewish Thought and his name is Rabbi Edward Feinstein.”

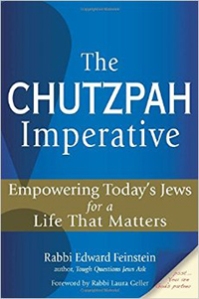

Feinstein, Rabbi Edward. The Chutzpah Imperative, Empowering Today’s Jews for a Life that Matters. Woodstock, Vermont. Jewish Lights. 2014.

The book begins, “We don’t ask enough of our Judaism…This is a Judaism of warm, ethnic sentimentality that demands very little of us and in returns offers little spiritual wisdom.” It ends, “If a new generation is to join this ancient tradition, they will join only for a message that is vital, significant, and timely. Chutzpah is that message. As the Talmud teaches, the task is great, the stakes are exceedingly high—not only the future of the Jewish people, but also the survival of humanity…But at this moment, our Judaism asks a great deal of us.”

The book grows from “We don’t ask enough of our Judaism” to “But at this moment, our Judaism asks a great deal of us.” The transformation is a re-centering and rereading the Jewish tradition as expressions of “chutzpah.” Chutzpah moves us from “ask too little,” to “asks a great deal of us.”

The book grows from “We don’t ask enough of our Judaism” to “But at this moment, our Judaism asks a great deal of us.” The transformation is a re-centering and rereading the Jewish tradition as expressions of “chutzpah.” Chutzpah moves us from “ask too little,” to “asks a great deal of us.”

Eddie gets the problem. It is of course the insights of the new generation:

The ideology of survival wore thin. Young Jews began asking startling new questions: Why? Why survive? Why be Jewish? Why marry Jewish? Why raise children Jewish? Their parents responded by reflexively citing the horrors of the Holocaust, but the kids turned away unmoved. The double negation—anti-anti-Semitism is not a foundation to Jewish life.

Therefore, the challenge of the Rabbi, the Jewish Educator, and the Jewish communal service worker is to redefine the meaning of being Jewish. Eddie does this in a brilliantly conservative way (small “C”), by saying that the answer was here all along. He begins a radical rereading of the Jewish tradition (radical as meaning in “back to the root.”) as manifestations and rejections of Chutzpah. It centers on “Abraham challenged God while Job accepted his fate.”

Eddie defines chutzpah as

“…a celebration of human freedom, human possibility and human responsibility. Judaism is a way to live a heroic life, to construct a life devoted to values that are eternal, values of ultimate significance. The reward of Jewish life is walking the world with a profound faith that you matter, your life matters, your dreams matter.”

He contrasts Rabbi Mark Borovitz’s unpublished manuscript, “You Matter,” with the dictionary definition, “unmitigated effrontery or impudence; gall; audacity; nerve.” While Chutzpah, in the hands of others including Alan Dershowitz and Leo Rosten is a Jewish John Wayne posture; it is in Eddie’s careful retelling an extreme act of religiously holding the line. Abraham challenging God to save Sodom is his poster boy. Many others follow. This leads us to his first chapter, “How to Argue with God and Win.”

His second chapter, “The Road to Eden” starts with the story of his uncle Henry who was a Holocaust survivor who was moved by Elie Wiesel from silence to being a witness. Eddie says, “This is more than a survivor’s resilience. It is an expression of something deeper. God commanded Abraham, “Be a blessing.” (Genesis 12:2)…To experience the darkest evil and not to give up on the world reflects qualities of courage and character we call “chutzpah.” Here is a “because of the Holocaust” that doesn’t just justify the State of Israel, but leads to a dynamic redemption of the whole world.

“Egypt was God’s classroom, part of a radical pedagogy: to create an entire people committed to Abraham’s covenant—to pursue the divine dream of justice in the world, a people prepared to serve as a vessel of divine blessing to all humanity—God brings Israel to a world of ultimate cruelty, darkness, and evil. To cherish the dream of Eden, we must live the nightmare of Egypt.”

And we all say, “Chutzpah.” He continues his narrative and gets to:

“The Torah is the archetype of all road stories. The journey from Egypt to the promise represents the human journey from smallness to greatness, from selfishness and fear to a compassion and solidarity. This road story is the master narrative of Jewish life.”

We plunge on through Purim, the Talmud, the Temple, Rabbi Akiva, the Return to the Land, and more. We move over to Jewish though retelling and reworking Maimonides, The Zohar, Isaac Luria, and even Fiddler on the Roof as the gateway to Buber, Heschel and Solovitchick. Reaching a crescendo. “While,

“Into this confusing new mileu, the ancient myth (pagan) has reemerged with virulence. To a populace confounded by global political, economic, and environmental threats, the myth confides, “Your fate is determined by forces far beyond your comprehension and control. These problems of the world are intractable. They can be fixed.”

How? Chutzpah!

Part Two

It is nice to review a friend’s book—especially when it is excellent. But there are actually huge educational implications to what Rabbi Feinstein had done. Most educational revolutions start with technique. We have one going right now that is based on technology, experiential learning, and Project-Based Learning. Technique come first; then comes content. The Chutzpah Imperative is a breakthrough into the content of the future. The content it chooses is not new. The Torah stories, the most accessible Talmud, and modern Jewish thought. These are well known and often taught fragments of the tradition. What is new here, is not the pieces of information, but the ideology in which they are framed. Eddie didn’t invent the concept of being God’s partner, but here he has created a framework through which that concept can animate it and make it relevant.

First the Torah tells us: “God blessed them and God said to them, ‘Be fruitful and multiply, fill the earth and subdue it. (Gen. 1.28)’” After Adam and Eve eat from the tree of knowledge, God revises that statement. “The Eternal God took Adam and placed him in the Garden of Eden, to work it and to guard it. (Gen 2.15)” The midrash now underlines the difference between the two: “When God created the first human beings, God led them around the Garden of Eden and said: ‘Look at my works! See how beautiful they are—how excellent! For your sake I created them all. See to it that you do not spoil and destroy My world: for if you do, there will be no one else to repair it. (Ecc. Rabbah 1 on Ecc. 7.13)’” This is drawn together by Jeremiah, “For I know the plans I have for you, declares the Eternal, plans for welfare and not for evil, to give you a future and a hope. (Jeremiah 29:11)”

In modern thinking, we have appropriated the Kabbalistic notion of tikkun olam, through which people of faith change themselves and that results in a universal redemption. Tikkun Olam has become self-actualization filtered through Buber to become social action. It says, “God is broken. The world is broken. And each of us is broken. Our connection to God helps us heal ourselves which then heals the world and God.” From this popular kabbalism emerges the modern notion that “People are God’s partners—each of us is God’s partner.” This single notion is the foundation of Eddie’s concept of Chutzpah.

Rabbi Feinstein’s teacher Rabbi Harold Schuslweis utilized this concept when he taught, “Every time we use the words, ‘Barukh Attah Adonai…” (Praised are You, Eternal…) to praise God, we need to know that we are adding the words, “Through Me.” Praised are You, Eternal, who clothes the naked (through me). This makes every act of religious expression a social commitment to personal involvement in redemption. That is chuzpah underallis that Rabbi Feinstein defines and demands.

Every Bible story, every Talmudic teaching, every Jewish practices asks not for our subservience and calls out for Chutzpah. It makes us heroes in the story that ends with the world becoming a better place.

When we do Storahtelling—chutzpah. When we are experiential—chutzpah. Project-Based Learning—We Matter. The Flipped Classroom—We are God’s Partner. All service learning connects us to others, to God, and to our inner yetzer-ha-chutzpah. This book doesn’t tell us what to teach. It doesn’t call on us to change our teaching techniques. Instead it calls for a much more radical transformation, change in the framework that our techniques are used to addres—basic Jewish content. Eddie simply says, “What will dramatically change the impact Jewish education will make—is the meaning we bring to it.”

“If a new generation is to join this ancient tradition, they will join only for a message that is vital, significant, and timely.”